Heaven's Mirror: Quest for the Lost Civilization (1999)

by Santha Faiia and Graham Hancock

Hancock challenges orthodox history with extraordinary theories of a vanished early civilisation destroyed by a cataclysm … However heretical his arguments, his sweep through the ancient world is arresting and audacious.

Awe inspiring and enigmatic, the sacred sites and holy places of ancient man have stood mute for millennia – their secrets seemingly vanished with the civilisations that built them. Yet what mysteries would they reveal if they could speak? Is there something that connects these sites – a hidden key that will once and for all disclose the riddles of our past? What is the startling archaic connection entwining the sacred places of our world?

Evading the interpretation of generations of historians and archaeologists the true cryptic nature and purpose of these sacred centres has lain in waiting – secreted in myth and legend and encoded in the very design of the sites themselves …

Until now.

In Heaven’s Mirror best-selling author Graham Hancock continues his quest begun in the No. 1 International best-sellers Fingerprints of the Gods and Keeper of Genesis to rediscover the hidden legacy of mankind – the revelation that the cultures we term ancient were, in fact, the heirs to a far, far older forgotten civilisation, and inheritors of its archaic wisdom …

In this breathtaking work of archaeological and mythical detection, we trace the ancient web of sacred sites around the globe on a spectacular voyage, from the temples of ancient Egypt to the enigmatic statues of Easter Island, from the haunting ruins of pre-Columbian America to the splendours of Cambodia’s ancient capital, Angkor – in order to crack the code of our ancient ancestors.

Accompanied by his wife Santha Faiia – whose sumptuous photographs illuminate the quest – and exquisitely portray the wonder and beauty of the ancient sites – Graham takes the reader on a remarkable odyssey – of sunken cities, and hidden chambers, of myth and magic – and astounding archaeological revelations – which builds to a staggering conclusion forcing us to reconsider our conception of the origins of man.

Hancock’s decipherment of the secret doctrine passed down by initiates from time immemorial unearths an age-old system obsessed with the motions of the heavenly bodies … whose aim is to achieve, through arcane rituals performed in temples whose layout mirror the stars and constellations of the night-sky, … immortality.

This is more than a sequel to Fingerprints of the Gods – it is a plunge into the spirituality of the ancients – a search for the revelation of a secret …

… a secret written in the language of astronomy, and recorded in the very foundations of the holy sites of ancient man …

… a secret which speaks of a mysterious connection between earth and heaven …

… a secret which turns temples into stars and men into gods …

Heaven’s Mirror Chapter 4

In the Hall of the Double Truth

The ancient Egyptians believed that the deceased must journey after death through the eerie parallel universe of the Duat – which is at once a starry "otherworld" and a strange physical domain with narrow passageways and darkened galleries and chambers populated by fiends and terrors. On this journey the jackal-headed mortuary god Anubis would sometimes act as a guide and companion to the soul.

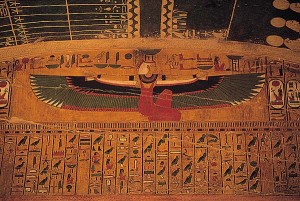

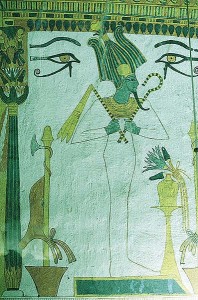

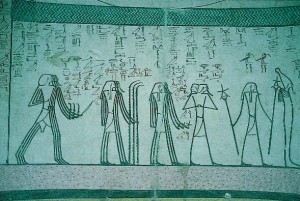

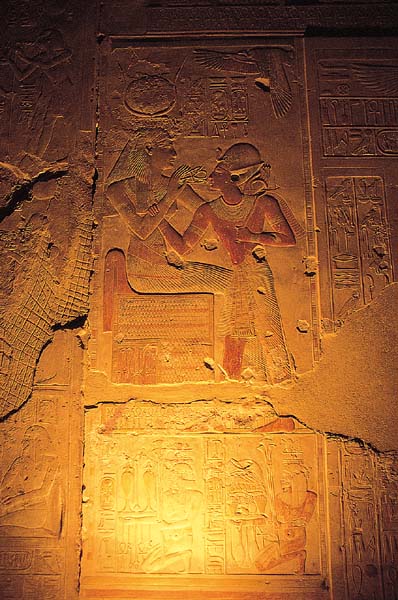

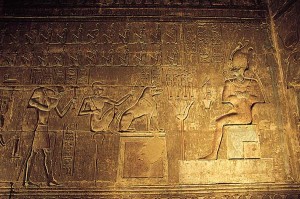

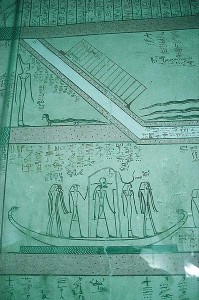

Detail from the "weighing of the soul", Deir el Medina. Top, some of the Assessors who hear the 42 Negative Confessions; left, ibis-headed Thoth, god of wisdom, records the verdict; centre, Ammit, the Eater of the Dead, the agency of the soul’s extinction; right, Osiris, Judge of the Dead and agency of the soul’s resurrection.

On the west bank of the Nile, opposite Luxor and Karnak, stands the strange and beautiful temple of Deir el Medina – which, like Edfu and Dendera, is a product of the final days of the once-remarkable civilization of ancient Egypt. Dedicated in the third century BC to Maat, the Egyptian goddess of cosmic equilibrium, its walls are inscribed with hieroglyphic texts expressing archaic religious and spiritual ideas.

The temple is built around an axis oriented south-east to north-west. We entered it through a gate in the south-eastern wall leading to a courtyard dominated by four elaborately adorned columns with floral capitals. Beyond these we passed into a central hall at the end of which we came to three doorways leading into three separate enclosed shrines. The southernmost of these shrines, dark and unprepossessing though it seemed at first, proved to contain a finely crafted and almost complete scene of what scholars describe as the Psychostasia, or Weighing-of-the-Heart (derived from the Greek psyche = soul, i.e. heart, and stasis = balance).

We took time to examine this scene, which consists of a chapter from the ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead, Reu Nu Pert Em Hru, literally the "Book of Coming Forth By Day", one of a large corpus of funerary texts copied and recopied at all periods of Egyptian history, that concerned themselves with "the freedom granted to spirit forms which survived death to come and go as they pleased".

Standing in the doorway of the shrine our eyes were drawn to the wall on our left containing an elegant relief of Ptolemy IV Philopator (ruled 221–205 BC), the Macedonian Greek Pharaoh on whose orders this Temple of Maat was built. Represented as a deceased soul, dressed in sandals and a simple linen kilt, this scene shows him being ushered into a spacious hall at the head of which, in partially mummified form, sits Osiris, the high god of death and resurrection, identified in the ancient Egyptian sky-religion with the great southern constellation of Orion.

The place to which Ptolemy has been brought is sometimes referred to as the Judgement Hall of Osiris, and sometimes as the Hall of the Double Maati – which translates as "the Hall of the Two Truths" or possibly "the Hall of Double Justice". It is not a place to which the soul was believed to have come immediately after death. Indeed, it could only be reached by those who were spiritually "equipped" to complete a long and hazardous post-mortem journey through the first five of the twelve divisions of the Duat – the fearful parallel dimension, shadowy and terrifying, filled with fiends and nightmares, that was believed by the ancient Egyptians to separate the land of the living from the kingdom of the blessed dead. The reader will recall that it was this same Duat, referred to as the Duat-N-Ba (the "netherworld of the soul"), that was said to have provided the model for the mysterious "primeval temple" spoken of in the Edfu Building Texts.

Ptolemy stands in the posture of salutation, left hand clenched across his right breast, right hand raised. On either side of him is a figure of Maat (hence "Double Maati") – a tall and beautiful goddess, sensual and full-breasted, wearing a head-dress topped by her characteristic ostrich-feather plume (the hieroglyph for "Truth"). The figure behind Ptolemy is empty-handed, and seems to be guiding him into the hall; the figure facing him holds in her right hand a long staff and in her left hand the hieroglyph ankh, the "cross" or "key" of life – the symbol of eternity.

In a double row at the side of the Hall 42 dispassionate figures crouch in the manner of scribes pouring over papyrus, each wearing the feather of Maat. These are the 42 Judges or Assessors of the Dead, before each of whom the deceased must be able to declare himself innocent of a particular wrong – the 42 so-called "Negative Confessions". For example:

No. 4 "I have not stolen";

No. 5 "I have not slain man or woman";

No. 6 "I have not uttered falsehood";

No. 19 "I have not defiled the wife of a man";

No. 38 "I have not cursed the God".

Having completed this stage of his examination, Ptolemy now finds himself confronted by an immense pair of scales beneath the arms of which are to be seen representations of Anubis, the jackal-headed guide of souls, and Horus the falcon-headed son of Osiris. One pan of the scales contains an object, shaped like a small urn, symbolizing the heart of the deceased, "considered to be the seat of intelligence and thus the instigator of man’s actions and his conscience". In the other pan stands the feather of Maat, symbolizing once again … Truth.

On this encounter of the heart with Truth everything hinges.

For at this moment an irrevocable Judgement will be passed which will offer the prospect of eternal life to the soul that triumphs, and eternal annihilation to the soul that fails. Beyond the scales is depicted the agency of the soul’s extinction: a monstrous hybrid, part crocodile, part lion, part hippopotamus, who is known as Ammit, the "Devourer", the "Eater of the Dead". And beyond Ammit, seated in majesty on his throne at the extreme right of the scene, our eyes are drawn again towards the mummified figure of the star-god Osiris, the agency of the soul’s resurrection.

Horus and Anubis test the scales, and proceed to measure the weight. Meanwhile, to the immediate right of the scales, between the deceased and the snarling, slavering jaws of Ammit, we observe the tall ibis-headed figure of Thoth, the "personification of the mind of god … the all-pervading and directing power of heaven and earth … the inventor of astronomy and astrology, the science of numbers and mathematics, geometry and land surveying". Mysteriously referred to in archaic inscriptions as "three times great, great", Thoth was the ancient Egyptian god of wisdom, "the recorder of souls", who – from Ptolemaic times onwards – would also come to be known to the Greeks under the name of Hermes Trismegistus ("Hermes the Thrice Great"). In the Judgement Scene he is shown as a powerful man dressed in a short tunic, wearing his characteristic avian head-mask. In his left hand he holds up a palette and in his right a fine reed pen.

Heart and feather stand poised in equilibrium, as they must if the soul is to be admitted to the afterlife kingdom of Osiris.

Horus confirms the balance.

Anubis announces the verdict.

Thoth records …

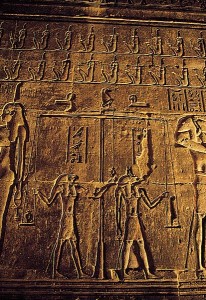

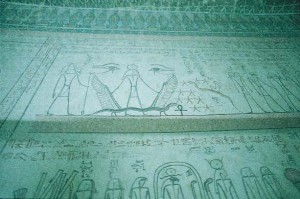

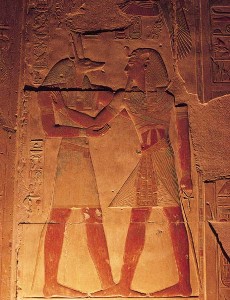

Thoth and Maat

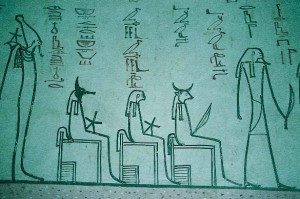

Hypostyle hall, Karnak: Thoth, the god of wisdom (ibis-headed, left) writes the name of Pharaoh Seti I (centre) on the tree of life. In later times Thoth became known to the Greeks as Hermes Trismegistus. He was the keeper of the knowledge that opened the door to immortality.

The deities Thoth and Maat are present in the earliest surviving scriptures of mankind – the ancient Egyptian Pyramid Texts of the third millennium BC – and continue to play pivotal spiritual and cosmic roles throughout the entire 3000-year span of Pharaonic history. Standing either side of Atum-Ra, the sun-god, as he sails the celestial ocean in his "boat of millions of years", they are portrayed in the Book of the Dead as eternal presences or principles whose function is to guide and balance the motion of the universe: "Thoth … Lord … self-created, to whom none hath given birth … he who reckons in heaven, the counter of the stars, the enumerator of the earth and of what is therein, and the measurer of the earth". Elsewhere we read: "The land of Manu [the West] receiveth thee [Ra, the sun-god] with satisfaction, and the goddess Maat embraceth thee both at morn and at eve … the god Thoth and the goddess Maat have written down thy daily course for you every day."

The word maat has many meanings in addition to "truth" – for example, "that which is straight", and, in the physical and moral sense, "right, real, genuine, upright, righteous, just, steadfast, unalterable", etc. Khebest maat is "real lapis-lazuli" as opposed to blue paste. Shes maat means "ceaselessly and regularly". Em un maat indicates that a thing is really so. The man who is good and honest is maat. And the truth, maat, "is great and mighty and it hath never been broken since the time of Osiris". It is perhaps not surprising that in some versions of the Psychostasia the goddess Maat, with her arms outstretched, takes the form of the scales themselves.

The feather and the heart, the two objects weighed in these scales, combine to convey a potent symbolic message. The former, as we have seen, is the type and symbol of the goddess herself, whilst it cannot be an accident that the latter, resembling a small vase with two handles, is not only used as the ancient Egyptian hieroglyph for "heart" but also forms the "determinitive" (defining sign) of the word tekh, "a weight". From this etymology – tekh through tehuti – some scholars derive the origins of the name Thoth, a derivation which the Egyptians themselves appear to have favoured. Let us also note in passing that the towering granite obelisks found in temples along the Nile were called tekhen by the ancient Egyptians – "a word of unknown origin" according to Martina D’Alton of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art.

As we shall see in later chapters, obelisks played a special role in the quest for immortality that was pursued for millennia by Egypt’s high initiates. From the remotest times this quest was intimately associated with the cult of Thoth, whose will and power were believed to keep the forces of heaven and earth in equilibrium: "it was his great skill in celestial mechanics," observed Sir E. A. Wallis Budge, "which made proper use of the laws (maat) upon which the foundation and maintenance of the universe rested".

After an exhaustive analysis of funerary texts from all periods of ancient Egyptian history, Budge also comments on the manner in which Thoth is ubiquitously portrayed as possessing "unlimited power" in the afterlife realm of the Duat. It is this power that is symbolized by his role as recording angel in the Judgement Scene. According to the Book of What is in the Duat (numerous representations of which survive in the tombs of Pharaohs from the Eighteenth Dynasty onwards): "The examination of the words takes place, and he [Thoth] strikes down wickedness – he who has a just heart, he who bears the words in the scales – in the divine place of the examination of the mystery of mysteries of the spirits."

But what exactly is meant by "wickedness" and what is the real nature of the mystery that is examined in the Judgement Hall of Osiris?

The Books of Thoth

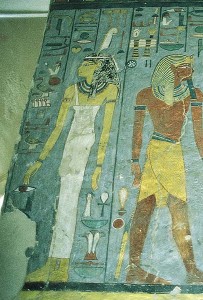

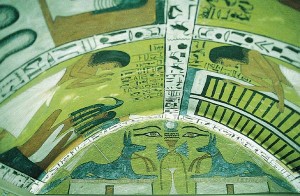

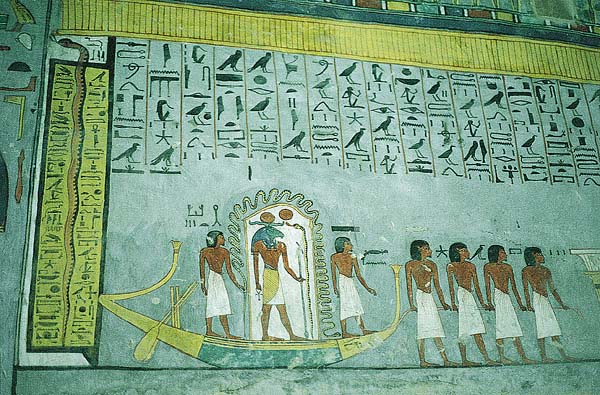

Detail from the Book of Gates, tomb of Rameses VI, Valley of the Kings. Like the Book of What is in the Duat, the Book of Gates depicts a journey through the Duat. The journey is by boat. In it, protected by the coils of a cosmic serpent, the sun god Ra stands flanked by the figures of "Mind" (fore) and "Magic" (aft). In the Book of Gates the Judgement Hall of Osiris occupies the Sixth Division of the Duat.

At stake in the Judgement Scene is something more than moral character. This is clear because questions pertaining to moral behaviour are addressed at quite an early stage in the proceedings by the soul of the deceased. This is the function of the 42 Negative Confessions. It follows, therefore, that the "weighing" of the heart must be an evaluation of something else – a measuring of some other quality or character or "truth" that the individual has been given the opportunity to add to during the course of his or her life. It is even possible that this may be the source of the Judgement Hall’s "Double Truth" – the concept that it is a place where two distinct and different levels of assessment must be undergone. This would explain why, as one eminent authority has observed:

the testing of the soul in the Balance in the Hall of Osiris is not described as the judging or "weighing of actions" [which the 42 Negative Confessions certainly are] but as utcha metet, the "weighing of words".

Additional light is shed on this curious formula when we remember that Thoth was regarded by the ancient Egyptians as a god who could teach "not only words of power but the manner in which to utter them". Knowledge of these "words" was believed to be essential if the deceased was to hope to complete his afterlife quest through all twelve of the "Divisions" of the Duat:

The words … must be learned from Thoth, and without knowledge of them, and of the proper manner in which they should be said, the deceased could never make his way through the Duat. The formulae of Thoth opened the secret pylons for him, and provided him with the necessary meat, and drink, and apparel, and repelled baleful fiends and evil spirits, and they gave him the power to know the secret or hidden names of the monsters of the Duat, and to utter them in such a way that they became his friends and helped him on his journey …

It was believed that Reu Nu Pert Em Hru, the Book of the Dead – "a sort of Baedeker for the transmigration of the soul" – was a composition of Thoth and that certain chapters of it had been written "with his own fingers". In addition numerous passages from the ancient texts have survived in which we learn that the wisdom god was also seen as the author of certain other "books" – books which anyone who sought the prize of immortality should attempt to discover during his lifetime: "I am endowed with glory, I am endowed with strength, I am filled with might, I am supplied with the books of Thoth and I have brought them to enable me to pass through …"

What the texts imply is that only he or she who has sought and found the books of Thoth can attain eternity. "How long have I to live" the deceased asks in some versions of the Judgement Scene. If all is well at the "weighing of words" Thoth replies by offering the coveted prize: "Thou art for millions of years, a period of life of millions of years …"

A Quest for Knowledge

According to Clemens Alexandrinus (Stromata VI) there were 42 books of Thoth, a number that provides a curious sense of balance with the "first truth" – the "weighing of actions" – examined by means of the 42 Negative Confessions. These books of the "second truth" – the "weighing of words" – were thought to be divided into seven categories covering, amongst other subjects, cosmography and geography, the construction of temples, the history of the world, the worship of the gods, medical matters, the hidden meaning of hieroglyphics, and treatises on astrology and astronomy including "the ordering of the fixed stars, the positions of the sun, moon and planets, the conjunctions and phases of the sun and the moon, and the times when stars rise".

The tradition of the books of Thoth persisted well into the Christian era, associated with Graeco-Egyptian temples such as Deir el Medina, Dendera, Edfu and the Temple of Isis at Philae where the ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs continued to be used and understood until as late as the fourth century AD. It is therefore hardly surprising that Clemens (AD 150–215) should have been aware of this tradition which was, indeed, set down afresh in writing in his adopted city of Alexandria at about this time. These writings, the so-called Corpus Hermeticum, repeatedly describe Thoth (the "Hermes Trismegistus" of the Greeks) as "he who won knowledge of all". He:

saw all things, and seeing understood, and understanding had the power both to disclose and to give explanation. For what he knew he graved on stone; yet though he graved them onto stone he hid them mostly, keeping sure silence [so] that every younger age of cosmic time might seek for them …

A quest, then, appears to have been envisaged for these stone tablets, or "books", of Thoth/Hermes. Indeed the Corpus Hermeticum leaves us in no doubt about this matter, telling us that the wisdom god used magic to postpone for as long as possible the rediscovery of his treasures of knowledge:

Ye holy books … which have been anointed with the drug of imperish-ability … remain ye undecaying through all ages, and be ye unseen and undiscovered by all men who shall go to and fro on the plains of this land, until the time when Heaven, grown old, shall beget organisms worthy of you.

Walter Scott, the translator of this passage into English, appends the following explanatory note concerning the term "organisms": "Literally ‘composite things’; that is, men composed of soul and body. After long ages there will be born men that are worthy to read the books of Hermes."

A Serpent which Cannot Die …

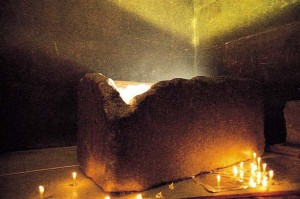

The urge to read them must be very old because it can be traced back deep into ancient Egyptian times, long before the compilation of the Corpus Hermeticum. For example, a papyrus of the Ptolemaic period preserves the story of a certain Setnau-Khaem-Uast, a son of Rameses II (ruled 1290–1224 BC), who sought for a "book written by Thoth himself". Information had come Setnau’s way, as a result of diligent research, that this book – which was said to contain a spell capable of granting immortality – lay concealed in an antique tomb in the Memphite necropolis (an extensive burial area stretching for some 35 kilometres along the west bank of the Nile from Meidum to Giza):

Setnau went there with his brother and passed three days and nights seeking for the tomb … and on the third day they found it. Setnau recited some words over it, and the earth opened and they went down to the place where the book was. When the two brothers came into the tomb they found it to be brilliantly lit up by the light which came forth from the book.

Another papyrus, this time from the Middle Kingdom (the Westcar Papyrus, circa 1650 BC), preserves an even older story from the time of Khufu (ruled 2551–2528 BC), the supposed builder of the Great Pyramid of Giza. The papyrus speaks of a "building called ‘Inventory’", located at the sacred city of Heliopolis (18 kilometres north-east of Giza), in which was stored "a chest of flint" containing a mysterious object that Khufu is reported to have "spent much time searching for". The context suggests it could have been a document of some kind because it recorded the "number of the secret chambers of the sanctuary of Thoth".

It is generally agreed that the Westcar Papyrus reports – or at any rate touches upon – real events. According to Professor I. E. S. Edwards it contains a "kernel of truth" and "was certainly a copy of an older document". Edwards further points out that Heliopolis, the site of the "Inventory Building", had been a centre of astronomical and astrological science in Egypt since times immemorial and that the title of the high priest of that city was "Chief of the Astronomers".

The Egyptologist F. W. Green expresses the opinion that the "Inventory building" could well have been a "chart room" at Heliopolis "or perhaps a ‘drawing room’ where plans were made and stored". Similarly, Sir Alan H. Gardner argues that "the room in question must have been an archive" and that Khufu "was seeking for details concerning the secret chambers of the primeval sanctuary of Thoth".

The central image of the Westcar Papyrus of some great secret of Thoth lying sealed away in a box is repeated in another text which tells how the wisdom god had deposited one of his books "in an iron box in the middle of the Nile at Coptos" (an ancient site some kilometres to the north of Luxor):

The iron box is in a bronze box, the bronze box is in a box of palm-tree wood, the palm-tree wood box is in a box of ebony and ivory, the ebony and ivory box is in a silver box, the silver box is in a gold box … The box wherein is the book is surrounded by swarms of serpents and scorpions and reptiles of all kinds, and round it is coiled a serpent which cannot die.

Last but not least amongst many similar sources that we could cite, there is a Coffin Text, circa 1900 BC, that speaks of the journey of the soul towards immortality. "I open the chest of Thoth", states the deceased, "I break the seal … I open what the boxes of the god contain, I lift out the documents …"

So there is a sense in all of this that what is weighed in the Judgement Scene at the "weighing of words" must in some way have to do with the possession of knowledge by the deceased, the kind of knowledge that can be inscribed on to tablets of stone or written down in books and "documents".

The Word

Like so many of the other funerary and rebirth texts of ancient Egypt, the Coffin Texts are manuals to guide the afterlife journey of the soul – the terrifying quest in the dark valley of the Duat that culminates with the Judgement Scene. The texts are so called because they were inscribed inside coffins, presumably so as to be easily accessible to the dead. They date from the First Intermediate Period (2134–2040 BC) and were particularly favoured during the Twelfth Dynasty (1991–1783 BC). In the early spells we read:

The young god [the deceased entering the afterlife kingdom of Osiris having found immortality] is born of the beautiful West, having come here from the land of the living; he has got rid of the dust which was on him, he has filled his body with magic, he has quenched his thirst with it … he has mastered the land through what he knew.

In a later spell an almost identical formula occurs:

See, Your Majesty has come, you have acquired all power, and nothing has been left behind by you … You have filled your body with magic, you have quenched your thirst with it … you have mastered the land with what you know like those to whom you have gone down.

And later still we read of the triumph of the "equipped spirit" and may begin to guess as to what it is with which he is "equipped":

I have passed over the paths of Osiris; they are in the limit of the sky. As for him who knows this spell for going down into them, he himself is a god, in the suite of Thoth; he will go down to any sky to which he wishes to go down to. But as for him who does not know this spell for passing over these paths, he shall be taken into the infliction of the dead which is ordained, as one who is nonexistent.

Celestial Co-ordinates

Detail from the Book of What is in the Duat, tomb of Thutmosis III, Valley of the Kings. Astronomically, the Duat was located in the sky between the constellations of Orion and Leo, but it was also a parallel universe which was always depicted as a maze of narrow corridors and passageways and rising galleries and chambers, populated by monsters. Compare to the passageway system of the Great Pyramid, facing page.

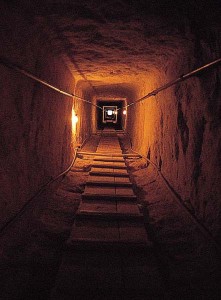

The descending corridor. Scholars have as yet failed to consider the possibility that the Pyramids and perhaps even the Sphinx of Giza could have been built as three-dimensional models of the "inner world" of the Duat-places of preparation in which initiates may have been selected to immerse themselves, perhaps in total darkness, perhaps for days, in order to gain foreknowledge of the afterlife realm. Yet there is nothing inherently improbable about such a proposition. We already know that the various ancient Egyptian "books of the dead" provide textual explanations and visual images of the Duat with the explicit purpose of preparing the deceased for the afterlife journey. To create a large-scale three-dimensional "model" of the Duat – a sort of simulated Netherworld – would be no more than an extension of this practice.

There can be no dispute that the equipped spirit was thought to master the land of the Duat with "what he knew". But what exactly was this knowledge? The suggestion in the texts that it was used to "go down to any sky" hints very strongly that astronomy might have been involved. This accords with what has been learnt concerning the astronomical interests of the priests of Heliopolis. It also makes sense of an important characteristic of the Duat to which few modern Egyptologists have paid attention: the afterlife region was not at any time conceived of by the ancient Egyptians as an "underworld" in the conventional Judaeo-Christian sense. On the contrary, as Dr R. O. Faulkner of the British Museum long ago observed, it is better described as a "netherworld" since it was "part of the visible sky".

In fact the Duat had very specific celestial co-ordinates. The first systematic attempt to chart these co-ordinates was undertaken in the 1940s by the Egyptologist Selim Hassan. Through a painstaking study of a mass of funerary and rebirth texts he established that the Duat had been conceived of by the ancient Egyptians as having been "localized in the eastern part of the sky" when the bright star Sirius – identified with the goddess Isis – and the stars of the Orion constellation – Osiris – were visible there in the pre-dawn. This was clear, he reasoned, from passages in the oldest texts which tell us: "Orion has been enveloped by the Duat while he who lives on the Horizon purifies himself. Sothis [Sirius] has been enveloped by the Duat while he who lives on the Horizon purifies himself." Hassan understood that such passages must have been based on observational astronomy:

as the sun rises and purifies himself in the Horizon, the stars Orion and Sothis are enveloped by the Duat. This is a true observation of nature, and it really appears as though the stars are swallowed up each morning by the increasing glow of the dawn. Perhaps the determinative of the word Duat, the star within a circle, illustrates this idea of the enveloping of a star.

More recently the author Robert Bauval has been able to pin down the location of the Duat in time and space still further with a crucial observation that Hassan missed. Because of the earth’s orbit, the background stars against which the sun is seen to rise each morning very slowly change throughout the course of the solar year. This means that the sun does not rise in concert with Orion and Sirius on every dawn, but only at certain and specific dawns (when the sun lies roughly between the earth and these stars). Furthermore, because of another characteristic motion of the earth, the season in which the "swallowing up" of Orion and Sirius takes place also very slowly changes. This motion is precession, which retards the moment of the sun’s arrival at any given stellar "address" at the rate of one degree every 72 years.

Precessional calculations for 2500–2300 BC – when the oldest surviving funerary texts from ancient Egypt were supposedly compiled – indicate that in that epoch the Duat could only have been regarded as being "active" (i.e. with Orion and Sirius rising just ahead of the sun) at around the summer solstice – the longest day of the year. At this time, and at no other season, would it have been believed to open its gates to the assembled souls of the dead. At one gate stood the constellation of Leo. At the other, divided from Leo by the glowing river of the Milky Way, stood Sirius, Orion and the constellation of Taurus. In 2500 BC this sacred portal in the heavens was said to "open" at the summer solstice because the sun rose in it at that time of the year. Today, because of the effects of precession, the sun "swallows up" Orion and Sirius at the autumnal equinox. In 10,500 BC phenomenon could only have been witnessed on the spring equinox.

Is it possible that the initiate’s skill at "going down to any sky" could be a reference to an ability to make precessional calculations – i.e. to harness intellect to imagination and to visualize the skies of former and future epochs?

Was it such knowledge that was believed to be sufficiently powerful to counterbalance the feather of Maat on the scales of Judgement and to triumph over nonexistence?

This is the word which is in darkness. As for any spirit who knows it he will live among the living … he will never perish … he will never die.

Superstition, or Science?

Undeniably powerful and even disturbing, the ideas conveyed in the funerary and rebirth texts of ancient Egypt have been described by Dr Stephen Quirke, Curator of the Department of Egyptian Antiquities at the British Museum, as belonging to an:

everlasting world … in which the endeavour to outlast eternity reaches its most self-conscious. [They] spell out the precise phrasing by which a dead person could be made into an eternally rejuvenated being. Today we call these ancient texts "funerary literature", but this technical term does them little justice: these are texts to transfigure the dead, to make human beings into immortal gods.

The ancient Egyptians themselves often called the texts sakhu, Quirke reports:

meaning recitations that would turn a person after death into an akh, "a transfigured spirit". The only alternative was to die and remain mut, "dead". These opposites of akh and mut are roughly equivalent to the European contrast between the blessed and the damned. As in the European tradition, paradise is envisaged in terms of light, and the word akh itself is one of a group in which the idea of light and radiance is paramount, such as the Egyptian for "horizon", akhet, the home of light. Faced with the alternative, the Egyptians concentrated all their resources into securing this eternal radiance.

In other words, although Quirke does recognize the lofty goal expressed in the texts – to transform human beings into immortal gods – he believes that it was sought for reasons that are largely psychological. Quite simply, he argues, the ancient Egyptians found the alternatives to eternal life – nonexistence, annihilation – too horrible to contemplate and therefore created an elaborate fantasy world which they imagined that their souls could enter and in which, if suitably "equipped", they hoped that they might win the prize of immortality.

In line with Quirke’s view, it has become customary amongst Egyptologists today to disparage the texts as little more than wishful thinking – "a strange accretion of spells and mumbo-jumbo … a reflection of humanity’s earliest supreme revolt against the darkness and silence from which none returns". Some scholars have even gone so far as to insist that:

In spite of their meticulous attention to detail in practical matters, the Egyptians of the Pyramid Age never evolved a clear and precise conception of the After-Life … The impression made on the modern mind is that of a people searching in the dark for a key to truth and, having found not one but many keys resembling the pattern of the lock, retaining all lest perchance the appropriate one should be discarded.

Similarly Dr Margaret Murray observes that "the horror of death is very marked in the religious texts of the Egyptians … Knowing that death is inevitable [the Egyptian] tried to prepare for it by a knowledge of the magic which would enable him to come back to the land and home he loved so well …"

It is the fundamental proposition of Heaven’s Mirror that matters are by no means so simple and that the Egyptian scriptures contain extraordinary material with an importance vastly deeper and darker than mere mumbo-jumbo, and far, far older than scholars have imagined.

Contents

Introduction: What is in the Great Beyond?

Part I: Mexico

- The Feathered Serpent

- On Earth as it is in Heaven

Part II: Egypt

- Sancturaries of the Cosoms

- In the Hall of the Double Truth

- Hidden Circles

- Mystery Teachers of Heaven

Part III: Cambodia

- Draco

- Churning the Sea of Milk

- Master Game

- Eliminating the Impossible

- Still Point in Heaven

Part IV: The Pacific

- Fragments of a Broken Mirror

- Island of the Sorcerers

- Spider’s Web

Part V: Peru and Bolivia

- Castles of Sand

- The Mystery and the Lake

- The Stone at the Centre

Conclusion: The Fourth Temple

References

Index